Writing: Giving Feedback or "Critiques" (Part 3)

Part 1 is found here and Part 2 here.

Continuing on from the previous posts about what are the aspects of critiquing one must be aware of, this week I'm going to show you the different ways a critic can deliver the goods and bads of a piece of writing. This list is by no means exhaustive and there is no one size fits all for giving feedback, and I'd love to hear about any other different ways you've come across.

How it's done: literally what it says on the tin. You give one good point about the writing (the bread), then one criticism or suggestion of improvement (the filling; not necessarily "the bad"), and finish off with a good point (the bread). This can describe the entire bulk of your critique (a big slab of bread, a big dollop of filling, then a big slab of bread) or you can do several serving of bread-filling-bread.

One of the commonest ways of delivering feedback. It's not difficult to do and some people find it easier to give and easier to take, because the criticism is sandwiched between praise and therefore reduces the harshness of the impact. It also reinforces the fact that everyone has their good points that they should know to continue (but sometimes they don't realise what they're already doing is good!) and that every piece of writing has positives and negatives.

For others, because the criticism is sandwiched between the praise, the recipient places more attention upon the 'good bits' and neglect the 'bad bits', because "hey, because there are more praises than criticisms, I must be doing well, right?" So some critics feel the shit sandwich devalues the feedback.

Or on the other extreme end of the spectrum, the recipient places more attention on the 'bad bits' and the praise goes entirely over their head. Some may argue the first slice of bread acts as a warning sign that bad news is about to be delivered, so the recipient becomes deaf to both the first praise as well as the last praise, honing only onto the negative part.

Personally, I like it. It's simple, it preserves ego, it encourages establishment of teamwork, and it's a method a lot of people are used to. I alter it slightly when I critique so that I start with praise, then I deliver criticism, then I finish with an overall view, focusing mainly on the positives again with some reminders of negatives (e.g. There are some areas where head-hopping should be tidied up, as I mentioned earlier, and I think you should focus more on character development rather than so much on the action. Overall I think...), but I always end on something positive.

Continuing on from the previous posts about what are the aspects of critiquing one must be aware of, this week I'm going to show you the different ways a critic can deliver the goods and bads of a piece of writing. This list is by no means exhaustive and there is no one size fits all for giving feedback, and I'd love to hear about any other different ways you've come across.

The Shit Sandwich

A.K.A the Feedback Sandwich.How it's done: literally what it says on the tin. You give one good point about the writing (the bread), then one criticism or suggestion of improvement (the filling; not necessarily "the bad"), and finish off with a good point (the bread). This can describe the entire bulk of your critique (a big slab of bread, a big dollop of filling, then a big slab of bread) or you can do several serving of bread-filling-bread.

One of the commonest ways of delivering feedback. It's not difficult to do and some people find it easier to give and easier to take, because the criticism is sandwiched between praise and therefore reduces the harshness of the impact. It also reinforces the fact that everyone has their good points that they should know to continue (but sometimes they don't realise what they're already doing is good!) and that every piece of writing has positives and negatives.

For others, because the criticism is sandwiched between the praise, the recipient places more attention upon the 'good bits' and neglect the 'bad bits', because "hey, because there are more praises than criticisms, I must be doing well, right?" So some critics feel the shit sandwich devalues the feedback.

Or on the other extreme end of the spectrum, the recipient places more attention on the 'bad bits' and the praise goes entirely over their head. Some may argue the first slice of bread acts as a warning sign that bad news is about to be delivered, so the recipient becomes deaf to both the first praise as well as the last praise, honing only onto the negative part.

Personally, I like it. It's simple, it preserves ego, it encourages establishment of teamwork, and it's a method a lot of people are used to. I alter it slightly when I critique so that I start with praise, then I deliver criticism, then I finish with an overall view, focusing mainly on the positives again with some reminders of negatives (e.g. There are some areas where head-hopping should be tidied up, as I mentioned earlier, and I think you should focus more on character development rather than so much on the action. Overall I think...), but I always end on something positive.

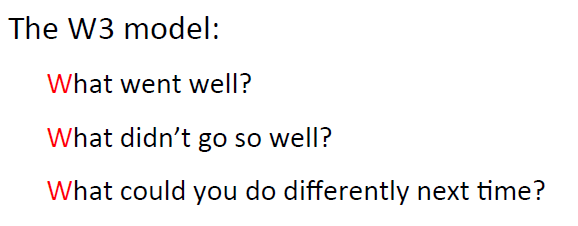

W3 Model

In critiquing, this is a different way of delivering feedback compared to the shit sandwich. Based on the three questions in your head, you highlight the pros, the cons, and also suggestions on improvement. If face-to-face, you can encourage the recipient to reflect on those questions themselves.

Remember, telling people "your tenses are all over the place and your characters come across as fake" may well emphasise their pitfalls, but, without suggestions for improvement, often that kind of feedback just damages ego without being very helpful. Just something simple such as "if you want to improve on tenses, one way of doing this is..." or "focus on what your characters really want and write their actions based on that, not what the plot dictates. You'll find the people more relatable and realistic that way."

Pendleton's 'Rules'

(From Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P (1984) The consultation: an approach to learning and teaching. OUP, Oxford)

Pendleton's 'rules' is pretty much the W3 model but integrates both the recipient's views as well as the critic's. This takes more time, but the interaction builds rapport and emphasises the teamwork aspect of giving feedback. Even without working face to face you can easily start by replying to the critique request with "Can I just ask you to PM me your answers to these questions *insert W3 questions here* and then I'll send you my thoughts?"

First, the critic has to clarify factual details. As mentioned in Part 2, Point 8 of Ende's Principles state feedback should be "on decisions/actions versus assumed intentions/interpretations." Someone has commented recently on my story, "I'm not sure if it's intentional, but your character comes across as one who doesn't fit his role and it's hard to relate to him." Now, if I were trying to make him as a shirker with a personality that is cold and unlikeable, I've succeeded. In reality, that character is actually the teacher who has his best interest in his students and is meant to be the rock of the team -- so I've actually failed!

What the commenter (she's not even my critic, but her comment was most helpful!) has basically done is highlight something that didn't sit well with her, but clarified it with me in case it was mistaken. Cluttered sentences can represent a writer who doesn't have the full grasp of the English language; alternatively it can also represent a cluttered mind. What was the writer trying to achieve?

Next, you and the recipient both partake in the W3 Feedback. The result is this:

- Clarify Facts

- Recipient comments on pros

- Critic comments on pros

- Recipient comments on cons/areas for improvement

- Critic comments on cons/areas for improvement

- Both discuss areas to focus on to change

Traffic Lights

This is an alternative to the shit sandwich, which is also quick and helpful.

Red light is where you state something that the writer should stop. For example, they should stop head-hopping, or stop jumping in tenses, or stop the endless flashbacks. Try and prioritise the most important bit(s).

Yellow light is where you state something the writer should change. For example, they should slow down on the pacing because everything is developing too quickly, or they should try to show more than tell, or avoid starting consecutive sentences with the same word as it becomes repetitive.

Green light is where you state something the writer should continue. For example, they should continue showing us character interactions as it's good development, or interlacing the surroundings with actions so there isn't obvious info-dumping or the pace isn't altered, or keep up the sarcastic internal commentary by the MC because that's what makes him/her so endearing.

A variant of this is "Start, Stop, Continue". Basically what it says on the tin.

Miscellaneous

I also find phrasing certain criticism as questions not only makes it more palatable for the recipient, it also makes them think. For example, if the MC is acting out of character, one can say, "I don't understand why she went for the gun. If she's shy and untrained in weapons, wouldn't run?" or "Why did the character do *insert surprising out-of-character action here*?"

What to Give Feedback On

This may be a point some people are wondering. Now that I've covered principles of giving feedback and methods of delivering it, there remains the question of quite what we're delivering. You can remember the theories of critiquing and package it nicely, but the contents are the important parts. What should you comment on? The character? The setting? The story delivery? The grammar?

It's up to you as the critic. First of all, what part of the writing worked for you? Some points you may consider are:

- Structure of the story e.g. clear setting, clear characters, 'starting with the action' or inciting incident, obvious conflict, logical sequence of events

- Voice e.g. the main character's internal thoughts, the storytelling voice of the writer

- Content e.g. is there evident info-dumping? Is the exposition well-balanced? Are any bits too long-winded?

- Conflict e.g. is it original? Is it a fresh twist? Is it obvious? Is it tragic? Is the hook good?

- Characterisation e.g. is the character realistic? Relatable? Hateworthy? One-dimensional? Self-obessed? Are any of the traits intentional? What are their motivations?

A note about grammar and punctuation: as critics, we are not editors, whose job is to tidy up those sticky sentences and missing apostrophes. Of course, prose with poor English grammar and punctuation makes for difficult reading, but please don't nitpick on every missing full-stop. If the writing is jarring in that sense to the point where it distracts from reading, just write one quick sentence on it (something like "Consider tidying up some of your sticky sentences as the phrasing can be awkward and difficult to understand" or "Remember commas always come at the end of dialogue if ending with a speaking verb"), but don't harp on about it. It's not your job.

Credit goes to Jenny Rosen on Wattpad for passing on her experiences of critiquing that made the "What to Give Feedback On" part possible.

Final Words

Critiquing is a learning curve. I've learned so, so much in just under a year's experience of critiquing. I started off as one of those arrogant critics where I highlight every negative and never praise, thinking "Well, writers need a tough skin so they might as well develop it now." Well, I've learned now that's not the way to do it. I'm not a publishing house or an agent. I don't need to be so harsh, and putting people down does nobody any favours. The bottom line for critics, at least on Wattpad in my opinion, is to be nice and be helpful. If a piece of work is so poor you don't think you can even summon a nice sentence for it, don't critique it.

I hope this three-part blog post on critiquing has been helpful and informative. I reiterate the fact that I have no professional credentials and do not claim to be an expert in any shape or form. I relay my own experiences and what I have read and been taught in the hopes that my posts will be of benefit for fellow writers and critics. Remember, writing and critiquing is something we all will benefit from, and there is nothing more valuable to a writer than good old constructive criticism.

I had to, fairly recently, teach someone how to use em dashes (I was acting in the capacity of an editor and also a bit of a beta reader or critic). This writer had never heard of them before, and I ended up finding an authority to show that I wasn't just making it up out of whole cloth. I also taught them how to make them on a standard keyboard (alt-0150 –) As I recall this person also would shovel in exposition and very little of it evolved naturally. I ended up doing the questions and examples thing, e. g. an author who does this well is ___, or here's a way to rephrase ____.

ReplyDeleteBTW, I guess I'm a cautionary tale as this person didn't listen to a word I said. But hey, I just made up em dashes (apparently). :)

Oh... seriously? Never heard of em-dashes? I've never used them, myself, but... oh dear. I assume as there are beta readers, that book is going to be published?

DeleteBut that's a shame. One can easily look up things like this to confirm you're not making things up. Your "questions and examples" is a good way to phrase criticism, I think! :)